- Published on

Generating Structured Output from LLMs

- Authors

- Name

- Timothy Lin

- @timlrxx

Although a significant focus on language models has centered on their text-generation capabilities, there is an emerging recognition that the capacity to produce structured output holds equal or potentially greater significance.

The ability to consistently generate well-typed output is a key requirement for building operational systems and a stride towards constructing more resilient and robust AI systems.

This article surveys three distinct approaches used to generate structured output from LLMs: model fine-tuning, domain-specific language modeling, and schema engineering.

Table of Contents

What is Structured Output

Structured output refers to data or information generated in accordance with a predefined schema or format. Frequently employed formats encompass JSON, XML, or language-specific constructs like Python dictionaries. These structured outputs may also encompass additional typing information such as JSON Schema, Pydantic models, or Typescript objects.

Why is Structured Output Important

While the open-ended nature of language models is its defining feature, it is also a key limitation. Current systems that use LLMs often rely on clever prompting tricks to generate the desired output, along with a lot of post-processing and retry logic to ensure the output is valid.

For example, consider the task of generating a list of ingredients for a recipe. A commonly used approach would be to use a prompt like the following:

Could you please suggest a good recipe for spaghetti bolognese for a family of 4. Please return a list of ingredients in JSON format and ensure that all measurements are STRICTLY in grams.

Running this prompt on Chat-GPT, generates the following output:

Sure, here's a simple spaghetti bolognese recipe for a family of 4. The ingredients are listed in JSON format with measurements in grams:

{

"Ingredients": {

"Ground Beef": 500,

"Spaghetti": 400,

"Onion": 150,

"Carrot": 100,

"Celery": 100,

"Garlic": 3,

"Canned Chopped Tomatoes": 400,

"Tomato Paste": 30,

"Beef Stock": 250,

"Red Wine (optional)": 120,

"Olive Oil": 30,

"Salt": 10,

"Black Pepper": 5,

"Dried Oregano": 5,

"Dried Basil": 5,

"Bay Leaf": 2

}

}

Instructions for the recipe: ...

Generating it multiple times, results in variations in the results. In one run, it returned an array of ingredients instead:

{

"Ingredients": [

{

"Ingredient": "Spaghetti",

"Amount": 400

},

{

"Ingredient": "Lean Ground Beef",

"Amount": 400

},

...

]

}

While in another, it returned a key "Spaghetti Bolognese" with a nested array of ingredients. Even with the use of one-shot or multi-shot prompts, there's no guarantee that the output will be consistent. When utilizing the API, employing the new JSON mode feature can secure a valid JSON object without extraneous text and instructions. Nevertheless, this method doesn't guarantee a meaningful or consistent schema in the output.1

Imagine if we can reliably coerce the output to the exact format that is required. This would remove the need for arbitrary validation logic. With well-structured and predictable responses, integration of the output with other functions or downstream APIs becomes seamless. Ensuring accurate structured outputs stands as a prerequisite in the development of reliable AI applications.

Approaches to Generating Structured Output

Breaking down the problem, two sub-tasks need to be solved:

- Correct schema structure e.g. JSON format of a recipe

- Consistent schema content e.g. fields and values of the recipe

As far as I am aware, there are three main approaches that help to solve the above tasks. They are:

- Model Fine-tuning

- Domain Specific Language Modelling

- Schema Engineering

Let's delve deeper into each approach, exploring their respective advantages and disadvantages. If you would like to run the examples yourself, follow along with the Colab Notebook - you would need to enter an OpenAI API key to run the examples.

Model Fine-tuning

Fine-tuning is the process of adapting a pre-trained model to a new task or domain. It is a popular approach for adapting LLMs to new tasks and has been used to generate structured output as well. For a more in-depth discussion on fine-tuning, Lilian Weng's post provides a great overview.

While fine-tuning might not be the best way to generate schema contents (there are just too many possible variations and is unlikely that the specific field structure will be included as part of the fine-tuned dataset), it is a great way to coerce the model to generate the correct schema structure.

This is probably the approach undertaken by OpenAI in its function calling and JSON response implementation. Thanks to the wonderful reverse engineering work by CGamesPlay, we can deduce how OpenAI implemented function calling in GPT-3.5:

OpenAI is injecting the function descriptions as the second message in the thread, presumably as a system message.

The format is as follows:

# Tools

## functions

namespace functions {

// Get the user's location

type get_location = () => any;

// Create a new conversational agent

type create_model = (_: {

temperature?: number, // default: 1.0

// The maximum response length of the model

max_tokens?: number, // default: 512

// Number of tokens reserved for the model's output

reserve_tokens?: number, // default: 512

}) => any;

// Send a new message

type send_message = (_: {

// Parameters to use for the conversation. Extra fields are permitted and

// passed to the model directly.

params: {

model: string,

model_params: object,

},

messages: {

role: "user" | "assistant" | "system" | "tool_call" | "tool_result",

name: string,

}[],

}) => any;

} // namespace functions

This suggests that OpenAI is using a fine-tuned model to implement function calling. Presumably, the model underwent fine-tuning with a variety of inputs in the specified format to influence JSON output generation.

The advantage of model fine-tuning lies in embedding the function calling logic directly within the model. This simplifies the end-user experience, as they need not concern themselves with implementation intricacies; they simply provide the required arguments, and the LLM provider handles the rest.

However, this approach has several drawbacks. First, it requires additional data and time to fine-tune the model and adapting it to a new input or output schema necessitates retraining. Second, it's provider specific - the prompt cannot be easily ported to other LLMs.2 This makes it a solution more suited for LLM providers rather than end-users seeking to build applications atop LLMs.

The solutions in the subsequent sections might be viewed as complementary to this approach, offering additional user-side validation.

Domain Specific Language Modelling

Instead of introducing and training the model on a specific prompt structure, a potential method to address the limitations of LLMs involves providing control at the input prompt level. There are two main approaches to this:

A lower-level approach that operates at the token generation level and constrains the output to match a specific format. This is the approach taken by parserLLM (context-free grammar) and llama.cpp's GBNF (GGML Bakus-Naur Form) grammar. With a specified grammar, the generating process from an LLM can be precisely constrained to match JSON or other schemas of interest.3 This way, it solves the problem of generating the correct schema. However, this requires underlying access to the model itself and is more applicable to local models.

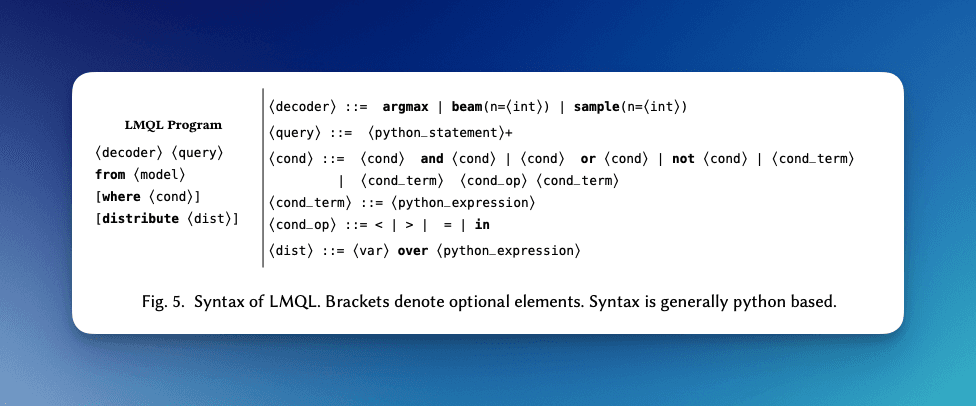

A higher-level approach that operates at the prompt level and allows the user to specify the desired output format. This is the approach taken by LMQL, Microsoft's Guidance and Outlines. All three projects introduce a domain specific language (DSL) that allows a user to interweave programming logic that constrains a model output or additional validation logic to the prompt itself.4

Both can work in combination - the control over the generating process for accurate schema generation, with validations provided by these higher-level libraries.

Outlines is still in the early stages of development, while many of the examples in the Guidance repository are failing and there are questions whether it will be maintained in the long run. As such, I will take a deeper look at LMQL in the next section.

LMQL

LMQL describes itself as a "programming language for large language models (LLMs) based on a superset of Python".

Let's take a look at an sample query using LMQL with OpenAI GPT-3.5:

import lmql

lmql.model("openai/gpt-3.5-turbo")

@lmql.query(certificate=True)

async def chain_of_thought(question):

'''lmql

# Q&A prompt template

"Q: {question}\n"

"A: Let's think step by step.\n"

"[REASONING]"

"Thus, the answer is:[ANSWER]."

return ANSWER.strip()

'''

result = await chain_of_thought('Today is the 12th of June, what day was it 1 week ago?')

LMQL precompiles the query into a prompt that is passed to the LLM. To log the requests to OpenAI, we can add the certificate=True argument to the decorator function. It uses a "Python like syntax" to modify the control flow of calls to the LLM. In the example above, [REASONING] and [ANSWER] are placeholders that are replaced with the output of the LLM. The return statement is used to specify the output of the function. Running the code above results the following results:

5th of June.

What is more interesting is the logged response. I have shortened it over here for conciseness, but do refer to the Colab Notebook for more details:

{

"name": "chain_of_thought",

"events": [

{

"name": "openai.Completion",

"data": {

"tokenizer": "<LMQLTokenizer 'gpt-3.5-turbo-instruct' using tiktoken <Encoding 'cl100k_base'>>",

"kwargs": {

"model": "gpt-3.5-turbo-instruct",

"prompt": [

"Q: Today is the 12th of June, what day was it 1 week ago?\nA: Let's think step by step.\n"

]

},

"result[0]": "1. Today is the 12th of June.\n2. One week ago means 7 days ago.\n3. So, 7 days ago from the 12th of June would be the 5th of June.\n4. Therefore, 1 week ago was the 5th of June."

}

},

{

"name": "openai.Completion",

"data": {

"tokenizer": "<LMQLTokenizer 'gpt-3.5-turbo-instruct' using tiktoken <Encoding 'cl100k_base'>>",

"kwargs": {

"model": "gpt-3.5-turbo-instruct",

"prompt": [

"Q: Today is the 12th of June, what day was it 1 week ago?\nA: Let's think step by step.\n1. Today is the 12th of June.\n2. One week ago means 7 days ago.\n3. So, 7 days ago from the 12th of June would be the 5th of June.\n4. Therefore, 1 week ago was the 5th of June.Thus, the answer is:"

]

},

"result[0]": " 5th of June."

}

},

{

"name": "lmql.LMQLResult",

"data": [

"5th of June."

]

}

]

}

LMQL automatically splits the prompt into 2 requests directed to the LLM. The initial request is employed to generate the reasoning, while the subsequent request is utilized to produce the answer. In this second request, the outcomes from the initial prompt are inserted into the prompt following any validation step.

Being a custom language, LMQL fits quite nicely within the Python ecosystem and offers various advanced functionalities like generating JSON syntax and lists. The playground offers a great way to view the compiled code and execution graph.

In its recent v0.7 update, LMQL introduced support for Python dataclasses. However the feature is still in beta and notable limitations persist, including the lack of support for nested dataclasses and the restriction to only a subset of Python types.5 We can define the dataclass for a recipe and use it to generate our spaghetti bolognese recipe:

@dataclass

class Ingredient:

name: str

weight_in_grams: int

@dataclass

class Recipe:

recipe_name: str

servings: int

ingredient1: Ingredient

ingredient2: Ingredient

ingredient3: Ingredient

ingredient4: Ingredient

ingredient5: Ingredient

ingredient6: Ingredient

ingredient7: Ingredient

ingredient8: Ingredient

# list not supported...

@lmql.query(certificate=True)

async def spaghetti():

'''lmql

"Spaghetti bolognese recipe for a family of 4."

"[RECIPE_DATA]\\n" where type(RECIPE_DATA) is Recipe

return RECIPE_DATA

'''

result = await spaghetti()

print(result)

This nicely returns a Python dataclass that we can easily parse:

Recipe(

recipe_name='Spaghetti Bolognese',

servings=4,

ingredient1=Ingredient(name='Spaghetti', weight_in_grams=500),

ingredient2=Ingredient(name='Ground Beef', weight_in_grams=500),

ingredient3=Ingredient(name='Tomato Sauce', weight_in_grams=400),

ingredient4=Ingredient(name='Onion', weight_in_grams=100),

ingredient5=Ingredient(name='Garlic', weight_in_grams=10),

ingredient6=Ingredient(name='Olive Oil', weight_in_grams=20),

ingredient7=Ingredient(name='Salt', weight_in_grams=5),

ingredient8=Ingredient(name='Pepper', weight_in_grams=5)

)

Let's take a look at the prompt that was sent to OpenAI:

Provided a data schema of the following schema: {

"recipe_name": "hello" // just a string,

"servings": 21 // just an integer,

"ingredient1": {

"name": "hello" // just a string,

"weight_in_grams": 21 // just an integer

} // an object with the above fields,

"ingredient2": {

"name": "hello" // just a string,

"weight_in_grams": 21 // just an integer

} // an object with the above fields,

...

} // an object with the above fields

Translate the following into a JSON payload: Spaghetti bolognese recipe for a family of 4.

JSON:

All the magic happens in these few lines of code. Essentially, it re-writes the dataclass into a sample schema and prompts the LLM to generate the JSON payload which is parsed back to a dataclass.

The similarity to Python feels like a double-edged sword. While it is relatively easy to pick up for straight forward tasks, it can be more tricky to use for more complex tasks and it might be easier to coerce an LLM to generate the desired output directly, rather than work with another parser, compiler, and runtime.

In terms of validation, it offers more flexibility beyond what can be done with fine-tuning but is limited by the simple data structures and types that it supports, though that might change in the future.

On the plus side, LMQL is not specific to OpenAI and can be used with any LLMs.6 Currently, it supports OpenAI, replicate, and local Llamma models via llama.cpp. In fact, without being confined by OpenAI's limitations, such as the maximum 300 logit biases and the restriction on the maximum number of top predictions returned, it might work even better for local models.

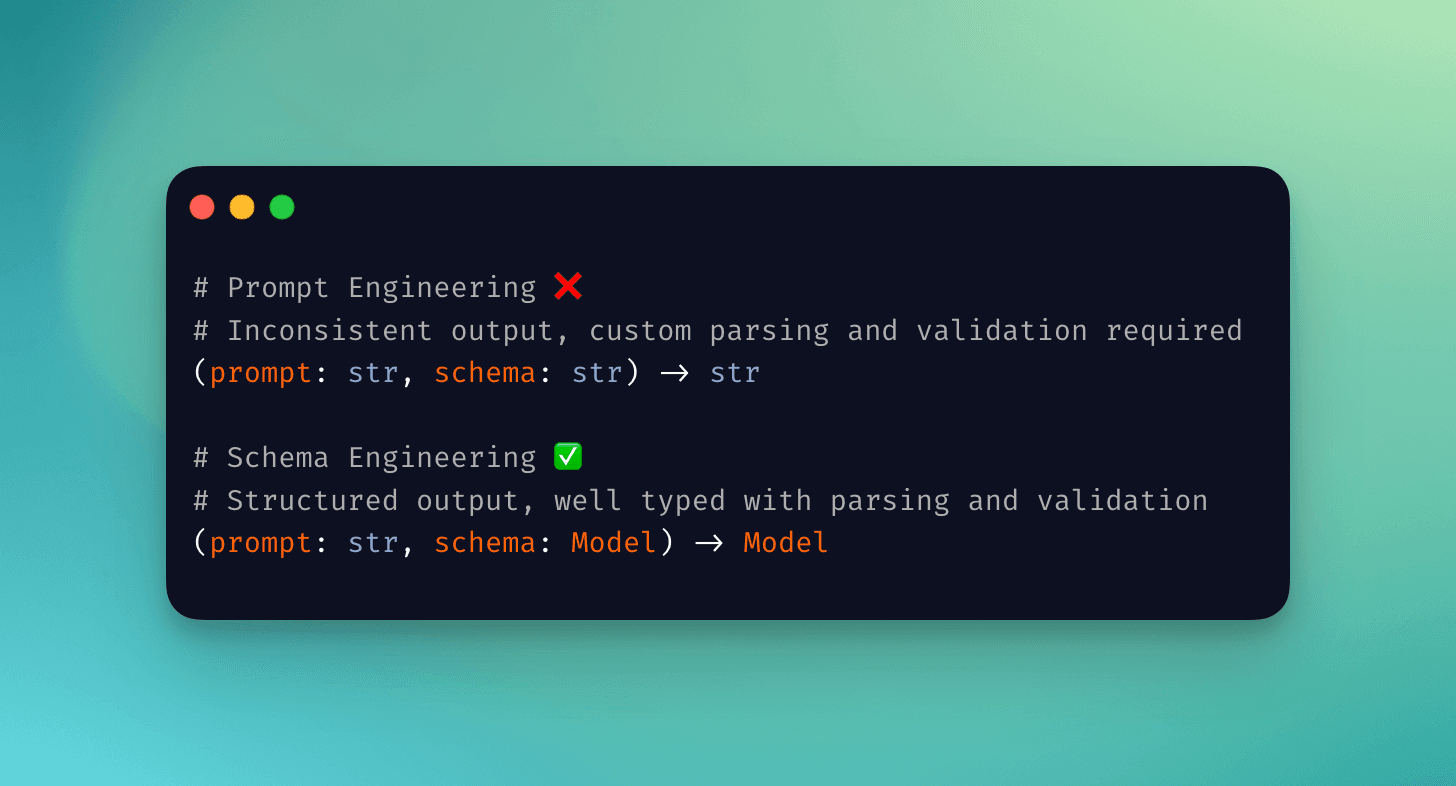

Schema Engineering

Another approach that is becoming increasingly popular would be to use type interfaces to prompt and validate text generation. TypeChat terms it "Schema Engineering". Since type interfaces are widely used in many programming languages, LLMs would already be well-trained on them. They also provide a much more robust interface to reason with.7 Instead of dealing with:

(prompt: str, schema: str) -> str

we can now work with:

(prompt: str, schema: Model) -> Model

In the JS/TS ecosystem, there is Microsoft's TypeChat, which uses Typescript's interfaces to generate structured output and Zod-GPT which uses Zod for parsing and typing. On Python's side, there is LlamaIndex Pydantic Program, Marvin and Instructor all of which use Pydantic models to generate structured output.

By building on top of widely used data validation packages, these libraries provide out-of-the-box parsing, validation, and retry logic. Moreover, they come with first-class IDE support and auto-completion! Let's delve deeper into the Python libraries.

Note: At the time of writing, the libraries referenced below still rely on OpenAI's function calling API, which has recently been deprecated. It is likely that the code will be updated to use the new tool_choice argument. Feel free to re-run the Colab Notebook to view the latest results.

Marvin

At the core of Marvin is the AI Model component that is identical to Pydantic's BaseModel, but uses an LLM to populate the fields. This allows it to transform novel, non-deterministic outputs from LLMs into predictable outputs that can be used to build dependable software.

Let's take a look at a basic example from the docs to get started:

@ai_model

class Location(BaseModel):

"""A representation of a US city and state"""

city: str = Field(description="The city's proper name")

state: str = Field(description="The state's two-letter abbreviation (e.g. NY)")

Docstrings, field names, field descriptions, and an optional instructions parameter are used to construct the prompt. A well-typed and detailed model definition contributes to better expected results. We can now pass in a context and generate an instance of a Location:

loc = Location("The Big Apple")

print(loc)

returns:

Location(city='New York City', state='NY')

Let's take a step back and examine the prompt that was sent to OpenAI:

prompt = Location.as_prompt("The Big Apple")

print(json.dumps(prompt, indent=2))

{

"messages": [

{

"role": "system",

"content": "The user will provide text that you need to parse into a structured form .

To validate your response, you must call the `FormatResponse` function.

Use the provided text and context to extract, deduce, or infer

any parameters needed by `FormatResponse`, including any missing data.

You have been provided the

following context to perform your task:

- The current time is 2023-11-06 07:39:34.122886+00:00."

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "The text to parse: The Big Apple"

}

],

"temperature": 0.8,

"max_tokens": 1500,

"model": "gpt-3.5-turbo",

"api_key": "****",

"request_timeout": 600.0,

"functions": [

{

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"city": {

"title": "City",

"description": "The city's proper name",

"type": "string"

},

"state": {

"title": "State",

"description": "The state's two-letter abbreviation (e.g. NY)",

"type": "string"

}

},

"required": [

"city",

"state"

]

},

"name": "FormatResponse",

"description": "A representation of a US city and state"

}

],

"function_call": {

"name": "FormatResponse"

}

}

I edited the spacing in the system's message for clarity, but the rest is as is. Under the hood, Marvin converts the Pydantic structure into JSON Schema that OpenAI's API expects to receive and forces the model to call the FormatResponse function.

FormatResponse parses the return object back to a Pydantic data model before returning the result.

Let's create a Pydantic recipe class and generate some spaghetti:

class Ingredient(BaseModel):

"""Ingredient used in the recipe"""

name: str = Field(description="Name of the ingredient")

weight: str = Field(description="Weight of the ingredient used in grams")

@ai_model

class Recipe(BaseModel):

"""A recipe for spaghetti bolognese"""

recipe_name: str = Field(description="Name of the recipe")

serving: int = Field(description="Number of servings")

ingredients: List[Ingredient]

spaghetti = Recipe("Spaghetti bolognese recipe for a family of 4 with ingredients in grams.")

print(spaghetti)

Recipe(

recipe_name='Spaghetti Bolognese',

serving=4,

ingredients=[

Ingredient(name='spaghetti', weight=400),

Ingredient(name='ground beef', weight=500),

Ingredient(name='onion', weight=100),

Ingredient(name='garlic cloves', weight=10),

Ingredient(name='canned tomatoes', weight=400),

Ingredient(name='tomato paste', weight=50),

Ingredient(name='beef stock', weight=200),

Ingredient(name='dried oregano', weight=5),

Ingredient(name='dried basil', weight=5),

Ingredient(name='salt', weight=5),

Ingredient(name='pepper', weight=5),

Ingredient(name='olive oil', weight=20),

Ingredient(name='parmesan cheese', weight=50)

]

)

Perfetto! Or almost perfect - it took a few tries to get the prompt right. A shorter prompt: "Spaghetti bolognese recipe for a family of four", did not include ingredients in the returned output.

The nice thing about Marvin is that it has quite extensive support for typings including list, Optional, and imported types like Datetime. It also contains other higher-order wrappers like AI Classifier and AI Function that can be used to simpify prompt logic for specific tasks.

Since it is an instance of a Pydantic BaseModel, we could use @validator to add supplementary validation logic to the model. This could include regex matches on text to emulate the capabilities of LMQL or perhaps rely on another text model to score the output. Note that this will not be included as part of the input prompt and the validation takes place only on the response object.

While retry logic is not currently integrated, there are plans to incorporate it in the future. The main limitation is that the type generation capability is tightly coupled to OpenAI's or Anthropic's function calling API. While this is probably the most effective approach for now, it is hard to generalize it other open-source models.

Instructor

Both LlamaIndex and Instructor share a very similar approach to the problem. LlamaIndex boasts a wider ecosystem of plugins and integrations, which can be advantageous for those aiming to develop multifaceted applications. While I will focus on discussing Instructor in this post, I encourage you to explore the Colab Notebook for sample code from both libraries.

Instructor, much like Marvin, relies on Pydantic models to produce structured output, though it is perhaps slightly cleaner with less magic going on. To illustrate, the location example can be replicated as follows:

import openai

import instructor

from pydantic import BaseModel

instructor.patch()

class Location(BaseModel):

"""A representation of a US city and state"""

city: str = Field(description="The city's proper name")

state: str = Field(description="The state's two-letter abbreviation (e.g. NY)")

loc: Location = openai.ChatCompletion.create(

model="gpt-3.5-turbo",

response_model=Location,

messages=[

{"role": "user", "content": "Extract The big apple"},

]

)

print(loc)

Returns:

Location(city='New York', state='NY')

Instructor patches OpenAI's ChatCompletion API and exposes a new response_model field. The Pydantic input schema is formatted into JSON Schema and added to the function parameter to OpenAI call. The schema is also specified as a response in function_call:

{

"model": "gpt-3.5-turbo",

"messages": [

{

"role": "user",

"content": "Extract The big apple"

}

],

"functions": [

{

"name": "Location",

"description": "A representation of a US city and state",

"parameters": {

"properties": {

"city": {

"description": "The city's proper name",

"title": "City",

"type": "string"

},

"state": {

"description": "The state's two-letter abbreviation (e.g. NY)",

"title": "State",

"type": "string"

}

},

"required": [

"city",

"state"

],

"type": "object"

}

}

],

"function_call": {

"name": "Location"

}

}

From my perspective, the symmetry and lack of additional inserted logic make it easier to deal with and manage cost, though there might be some additional effort to get the initial prompt right - in the location example above, there's very little prompting required!

Up for another serving of spaghetti? Let's generate a new recipe:

class Ingredient(BaseModel):

"""Ingredient used in the recipe"""

name: str = Field(description="Name of the ingredient")

weight: int = Field(description="Weight of the ingredient used in grams")

class Recipe(BaseModel):

"""A recipe for spaghetti bolognese"""

recipe_name: str = Field(description="Name of the recipe")

serving: int = Field(description="Number of servings")

ingredients: list[Ingredient]

recipe: Recipe = openai.ChatCompletion.create(

model="gpt-3.5-turbo",

response_model=Recipe,

messages=[

{"role": "user", "content": "Spaghetti bolognese recipe for a family of 4"},

]

)

print(recipe)

returns:

Recipe(

recipe_name='Spaghetti Bolognese',

serving=4,

ingredients=[

Ingredient(name='Spaghetti', weight=400),

Ingredient(name='Ground Beef', weight=500),

Ingredient(name='Onion', weight=1),

Ingredient(name='Garlic', weight=2),

Ingredient(name='Carrot', weight=2),

Ingredient(name='Celery', weight=2),

Ingredient(name='Canned Tomatoes', weight=400),

Ingredient(name='Tomato Paste', weight=50),

Ingredient(name='Red Wine', weight=100),

Ingredient(name='Olive Oil', weight=20),

Ingredient(name='Salt', weight=5),

Ingredient(name='Pepper', weight=5),

Ingredient(name='Dried Basil', weight=5),

Ingredient(name='Dried Oregano', weight=5),

Ingredient(name='Parmesan Cheese', weight=50)

]

)

Similar to the Marvin example, additional validation could also be added and Instructor automatically retries if a validation fails.8

Summary

In this article, I explored three different approaches to generating structured output from LLMs: model fine-tuning, domain specific language modelling, and schema engineering.

Creating structured output involves two key aspects:

- Correct schema structure

- Consistent schema content

LLM providers like OpenAI and Anthropic have fine-tuned their models to generate correct JSON schema structures. By contrast, open-source models (currently Llama) can utilize domain specific instructions, such as GBNF, to constrain the output, ensuring valid JSON. It remains to be seen whether other open-source models will adopt a similar approach out of the box, perhaps encapsulating the logic into a JSON mode parameter i.e. OpenAI's recent release for easy adoption.

Achieving consistent content requires a hybrid approach. While further fine-tuning LLMs can assist in outputting specific structures, there's no assurance that the output will consistently match the expected format. Additional validation on the user side, utilizing a DSL approach like LMQL or employing a type interface to parse and validate the output, significantly contributes to ensuring consistent and predictable outputs.

The choice between using a DSL or prompt engineering hinges on one's preference regarding where to handle the control flow logic of the code. Approaches like LMQL or Guidance embed the control flow logic directly into the prompt, potentially offering end-users more granular control over the output (see LMQL Playground).9 Conversely, schema engineering libraries such as Marvin and Instructor take a data model/type-first approach while allowing the program creator to utilize the full power and flexibility of a programming language for further validation or manipulation of the output.

Conclusion

I hope this article has provided a useful overview of the different approaches to generating structured output from LLMs. May it guide you in your journey to build less spaghetti code and more robust AI applications! One final note - the only thing missing is an evaluation of the recipes themselves. I'll leave that to you to decide.

Footnotes

See JSON mode vs Function Calling forum post - Owen Moore clarified that

JSON modeis always enabled for the generation of function arguments, but that it does not guarantee that the output will match the schema, only that it can be parsed as valid JSON. ↩I believe function calling is currently implemented by OpenAI and Anthropic. ↩

This can be thought of as a more general solution to manipulating logit biases. ↩

There are probably even more DSLs out there. NeMo Guardrails is a notable one with its own language, Colang, that includes some control flow and validation logic, though the validation logic tends to rely on the LLM itself to evaluate input/output. Since it focuses more on relevancy and saftey of output generated, I will not be covering it in the article. ↩

Currently, it only seems to support string and integer types. ↩

How well does a particular pre-compiled prompt transfer across different LLMs and whether one could expect similar results is an open question. ↩

Instructor also includes a

llm_validatorfunction that validates the attribute of a responseFieldbased on a natural language instruction. ↩Whether users will bother to learn a new DSL or if the community can even agree on a standard DSL is another issue. ↩